When the news of Christopher Columbus' early trip and discoveries in the new world in 1492 spread through the courts of Europe, England and France see the opportunity to claim for themselves some of the potential vast wealth that these new lands have to offer.

France's earliest thrust

to claim some of the new world for itself is in the Spring of 1534, when

Francis I sends a French sailor, Jacques Cartier, from St. Malo, France,

April 20, with sixty-one men. Arriving in less than three weeks to Canada,

Cartier disembarks and plants a 30 foot wooden cross to which he has attached a

shield bearing the fleur-de-lis and on which he has carved the words Vive le

Roy de France (Long Live the King of France). He does not linger long in

the new land, leaving quickly for France, bringing back with him two young

Indian braves, sons of the local chief.

France's earliest thrust

to claim some of the new world for itself is in the Spring of 1534, when

Francis I sends a French sailor, Jacques Cartier, from St. Malo, France,

April 20, with sixty-one men. Arriving in less than three weeks to Canada,

Cartier disembarks and plants a 30 foot wooden cross to which he has attached a

shield bearing the fleur-de-lis and on which he has carved the words Vive le

Roy de France (Long Live the King of France). He does not linger long in

the new land, leaving quickly for France, bringing back with him two young

Indian braves, sons of the local chief.

The following year, on May 19,1535, Cartier leaves France with

three ships. He leaves with 110 men and the two Indian braves he had brought to

France the previous year.

Cartier's mission is to spend the winter in the new land. He

arrives at the mouth of the St-Lawrence River in July, and begins the journey

up the great river in search of new routes to China and India. When he arrives

at the Indian village of Stadacona, built on the high promontory of what is now

Quebec, Cartier is warned by the local Indian chief of the perils that await

him farther up the river. Cartier decides to proceed on another river, leaving

the other two ships at Stadacona. Toward the end of September, Cartier nears

the important Indian trading center at Hochelaga, now Montreal, and the Lachine

Rapids that prevent any farther advance along the St-Lawrence. Cartier and his

party go ashore at Hochelaga, visit with the local Indian tribe, exchanging

trinkets for safe passage in the area and gaining information about the land

beyond the Rapids. By mid-October Cartier is back at Stadacona to prepare for

the winter stay. The winter proves disastrous for the French; many die of

scurvy and are buried in the drifted snow. In the Spring of 1536, Cartier

leaves for France because so many of his sailors have been lost during the

bitter winter.

Cartier makes a third trip to the new world in 1541, with the hope

of establishing a permanent French colony. He returns to the area of Stadacona

and establishes a settlement, Charlesbourg Royal. The attempt at colonization

at Charlesbourg is a failure due to the discord among the settlers, many of

whom are misfits, and to the disagreements between Cartier and the Lord of

Roberval, who had been named to head the settlement by the King. Cartier

returns to France the same year, and the settlement is finally abandoned the

following year.

No other serious attempt at colonization

is made by France in the 16th century, although fishing and fur trading

expeditions continue.

No other serious attempt at colonization

is made by France in the 16th century, although fishing and fur trading

expeditions continue.

Samuel

de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain

is born near La Rochelle

in France and spends his early years in the army. After the death of Philip II

of Spain and peace between Spain and France, Champlain finds employment on a

French ship in the service of Spain. In 1599, he sails to the Spanish colonies,

visits Mexico City, makes his way to the Pacific Ocean, all the time keeping

notes and plotting numerous maps.

In 1601, Champlain

returns to France where he seeks and receives an audience with the Calvinist

king of France, Henry IV. Champlain describes to the king the greatness and the

wealth that he has seen in the Spanish colonies. Henry IV is so impressed that

he keeps Champlain at court as the royal geographer, gives him a pension, and

makes him a noble

In 1603, Champlain is

sent by Henry IV to chart the territories that France claims in the northern part

of the new world. Champlain executes his mandate faithfully, bringing back to

the court and to the commercial sponsors detailed charts of the territories

from the mouth of the St-Lawrence River to Montreal.

The following year, in

March of 1604, Champlain leaves leaves France with two ships and 120 workmen to

establish a permanent colony for France. The expedition is sponsored

financially by the king. The ships make their way to the coast of Nova Scotia

where Champlain begins to look for the best site on which to establish the

settlement. The convoy finally enters the Bay of Fundy where Champlain finds a

spacious and landlocked harbor he calls Port Royal. In June, at the end of the

bay, at the mouth of the St-Croix River, Champlain founds the colony on a small

island that provides security from any sudden attack. The colony endures until

it is destroyed in May 1613, by Samuel Argall who sails up the eastern coast

from the English Protestant colony at Jamestown, Virginia seeking out French

Catholic settlements. Argall captures some settlers and sails away with them

after destroying Port Royal. Other settlers scatter into the woods.

Later they would gather

again with more men at what is now Quebec, protecting from the English because

it is far inland and on high cliff. Champlain rules in the manner of an Indian

chief and deals with the natives in this manner.

A

Deadly Blow

Champlain loses one of

his major financial supporters when the Protestant King Henry IV is

assassinated by a Catholic fanatic. This event places a strain on Champlain's

ability to keep the budding colony at Québec growing. Champlain makes numerous

trips across the Atlantic to seek financial support for Québec.

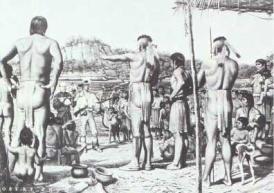

Many missionaries come to the new world in those early

days. Both Jesuit and Recollet

missionaries come to the territories claimed by France with the

"mission" of converting the "savages" to Christianity.

Missions are scattered from the shores of the St-Lawrence River to those of the

Great Lakes.

The

First Fall of Québec City

No supplies reach Québec

the following winter due to the persistent raids by the English privateers

known as the Kirke brothers. Finally, in July 1629, the Kirkes land at Québec

with a hundred and fifty men. The English capture the capital of New France on

July 20th. They drive out the settlers and the missionaries, burn the

habitation, and build a fort on the cliffs of the Cap-aux-Diamants overlooking

the St-Lawrence River. Champlain is carried off as a prisoner of war and lands

in Plymouth, England on October 24, 1629. It is then that learns that England

and France had signed a peace treaty on April 24, 1629, before the capture of

Québec, a fact the Kirkes were well aware of at the time of their attack.

Champlain crosses over to France and convinces the King that France has lost a

vast and rich empire. France demands from England the return of New France and

Champlain returns to Québec City on May 23, 1633, as Governor of New France.

With him come two hundred new colonists recruited by the reactivated Company of

New France, Jesuit missionaries, and soldiers to defend the renewed French

colony.

The Western Frontiers - The Spread of Catholicism and the

Fur Trade

The Western Frontiers - The Spread of Catholicism and the

Fur Trade

France has two main

interests in the new world, exploiting the land for monetary gain, principally

through the trade in furs, and converting "the pagan savage souls" to

Catholicism. As mentioned earlier, missionaries had come with Champlain to

New France as early as 1615. The priests make contact with the Huron

Indians. Later it was the Jesuits priests who direct their attention to

the converting of the Hurons to Catholicism. The most famous example of these

endeavors is the establishment of the mission to the Hurons. The mission,

referred to as Sainte-Marie au Pays des Hurons, reaches its zenith in the late

1640's when it includes stables, workshops, medical facilities and lodgings. At

one time it houses as many as 66 Europeans as well as visiting Hurons.

In 1648 and 1649 the Iroquois

from Upper New York State, the dreaded enemy of the Hurons and the French

Americans, begin a systematic destruction of Huron villages in what is now

southern Ontario, killing the inhabitants and torturing and killing the French

missionaries. On June 14, 1649 the Jesuits set fire to Sainte-Marie to avoid

its desecration by the Iroquois. It is during this Iroquois reign of terror

that six of North America's eight martyrs are killed, among them St-Jean de

Brebeu. The remaining Hurons flee to Champlain’s capital in Quebec City, to the

islands in Georgian Bay, to the northern shores of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan

and even to Wisconsin.

Forgetting for the moment the desire for

empire and land, the other motivating force for opening up the frontiers of the

new world is the lure of profits from the fur trade and from providing supplies

and services to the French colonial regime and its military. In particular,

trading furs offers the opportunity for enterprising individuals to obtain

wealth not otherwise available from the trades or in farming. The quest for

this wealth and perhaps the quest for the greater individual freedom to be

enjoyed on the frontiers lead to the establishment of a vast empire on the

"western frontiers" of New France. Voyageurs and fur traders

from the St Lawrence settlements, principally Québec City, Trois Rivières and

Montréal, first open up much of the continent by following the northern water

routes through much of the northern great lakes of Superior, Huron and

Michigan. By the late 1600's they establish a trading network which extended

westward to the prairies of Canada and the United States, some say as far as

the Rocky Mountains, and northward to Hudson's Bay.

Marquette, the priest & Jolliet, the fighter discover

opportunity in Illinois

Louis Jolliet was born

in Quebec in 1645. He was the first important explorer born in North America

from European descent. He was taught at the Jesuit seminary in Quebec, but for

unknown reasons left the order in 1667, and journeyed to France, probably

studying cartography there. The next year he returned to Canada, became a fur

trader and met Father Jacques Marquette.

Marquette was born

in 1637 in Laon, France. He became a Jesuit priest, and, on his own request,

was sent to Quebec in 1666. In 1668 he set up a new mission, at Chequamegon Bay

near the western end of Lake Superior. When the Huron Indians that he worked

among fled after Sioux attacks, he followed them and moved the mission on the

northern shore of the Straits of Mackinac.

Rumours

had been heared about a large river in the south (the Mississippi), and the French

hoped that this river would lead them to the Pacific and China. Louis Jolliet

was sent out to search for this river, and Marquette was chosen to be the

missionary of the expedition.

In 1673

Jolliet, Marquette and five others left on their journey to the Mississippi.

They followed Lake Michigan to Green Bay, canoed up the Fox River, crossed over

to the Wisconsin and followed that river downstream to the Mississippi.

The first

Indians they encountered were the Illinois, who were extremely friendly to the

explorers. They expressed their great happiness to have the French visiting

them, and provided them with a peace pipe or calumet to use for the

remainder of the journey.

As they

went further on along the river, they grew more and more convinced that it

flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, and not the Pacific. Yet they pushed on until

almost the mouth of the Arkansas near present-day Memphis. Here the Indians

told them that the sea was only ten days away, but also that hostile Indians

would be found along the way. They also noticed the presence of Spanish trade

goods among the Indians. Not wanting to be captured by Indians or Spanish, they

decided to return. They used an easier route now, shown by the Indians, up the

Illinois and then by way of the Chicago River to Lake Michigan.

In October

1674, Marquette went back to the Illinois, intending to live and preach among

the Illinois people. However, he did not manage to reach the village that year,

and had to winter near present day Chicago (Harlem Avenue). Arriving around

Easter 1675, he preached to a large number of Indian chiefs and braves.

However, his health was deteriorating. He decided to return north, but died of

dysentery before reaching the mission where he intended to spend his last days.

Jolliet's journal and map got lost when his canoe

overturned on the Montreal rapids. The only remaining record of the expedition

is an unfortunately rather short diary, reputedly written by Marquette. For

some time he clashed with the authorities about the proceeds of his trip, but

in 1679 he travelled up the Saguenay and Rupert rivers to spy on the British

positions around the Hudson Bay, and received Anticosti Island as a reward. In

1694 he made another journey, exploring the coast of Labrador and visiting the

Eskimos. He died in 1700, being lost on a trip to one of his land holdings.

Following military campaigns against the Iroquois in 1667, a

period of peace ensues between the French and the Iroquois nation. By the mid

1700's primary trade routes are firmly established linking the French

settlements on the St Lawrence River to a string of forts and trading posts

located on the western plains, the northern lakes and south along the Ohio and

Mississippi Rivers to the Gulf of Mexico. These include colonies at St. Louis,

Kaskaskia, Illinois, and a trading post at Chicagou.